Twelve Days 2013: Persistent Data Structures

Day Six: Persistent Data Structures

TL/DR

Persistent data structures have nothing to do with disks, durable storage, or databases. They’re an (externally) immutable collection born out of functional programming, but they have great use cases for any programming paradigm. Immutability helps greatly in multi-threaded environments, and regardless of the threading model used they’re a natural means of adding versioning and snapshot functionality to a collection. This proves useful for everything from synchronizing data in distributed systems to implementing an undo operation. Clojure relies on them extensively and they’re included in the standard libraries of many other functional languages.

High Level Overview

Persistent data structures can be “fully persistent” or “partially persistent.” Fully persistent data structures allow for changes to any previous version and keep track of those versions via a change graph. Partially persistent ones only allow for changes to the current state, but read-only access to any previous state. We’ll focus on partially persistent ones.

One of the simplest examples of a persistent data structure is a collection with copy-on-write semantics. If you’ve used java’s CopyOnWriteArrayList you’ve already seen this in action. Get operations are only slightly more expensive than ArrayList access (the backing array is volatile so there’s an mfence whenever it’s accessed, which happens once per get operation, and once for the entirety of an iteration). However, all operations that mutate do so by locking and copying the backing array in entirety before swapping out the old array for the new one. This ensures that any other thread working with the list or iterating over it will see a consistent view of the backing array. There’s two problems with this approach: 1) It’s prohibitively expensive if the collection changes frequently, and 2) it still relies on locks to mutate state. Before addressing concurrency, let’s see what we can do about the first problem.

Persistence via Path Copy

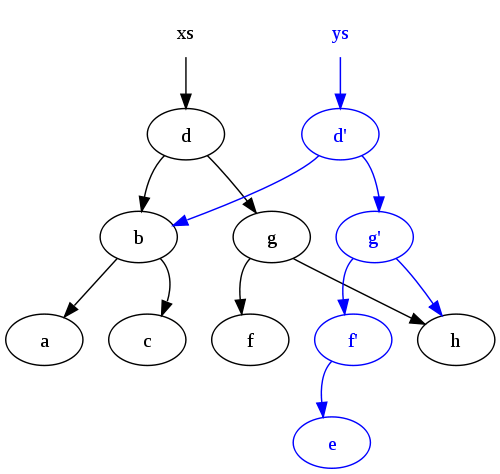

Without too much work we can do a little better than copy-on-write for most use cases via path copying:

We start by structuring our collection as a d-ary tree (or a trie if ordering matters). When we need to mutate state we copy all nodes along the path containing the mutation. We then work backwards from the point of the change, fixing up references along the way so that everything along the mutated path holds a reference to the newly created node reflecting our insertion/deletion.

You can represent pretty much any standard type of collection as a tree (maps, sets, lists…), albeit with some level of

inefficiency. For something like a vector the degenerate case is just a d-ary tree, where d is the length of the

vector, leading us back to the copy-on-write semantics described above. As such, the degree of branching trades off

between time complexity for access and mutation.

Real World

In practice, there are more complex but way more efficient ways to go. For arrays, an efficient implementation is described in this paper. CTries are efficient and concurrent implementations of hash array mapped tries. For further study, Rich Hickey, the creator of Clojure gave a very nice presentation on persistent data structures at QCon (Clojure uses them for all of its mutable collections). It’s worth noting that making lock free persistent collections is really hard without garbage collection, so this is one area where managed runtimes have a big advantage. What about atomic reference counting and shared_ptr? They’re pretty expensive and doesn’t scale well (especially on x86’s strong memory model), which is one of the reasons why java uses a graph tracing garbage collector instead of something more fine grained.

A Motivating Example

In my work with distributed systems, synchronizing state is almost always a core concern. How do you get a “late joiner” caught up with the current state of the universe? Reading from logs is one possibility. Another involves creating a snapshot whenever a client asks for it. Assume that you have a single threaded, event driven architecture in which the server handles one request at a time. Also assume that all messages have a unique sequence number (so gap filling and detecting missing messages for retransmission is handled elsewhere). Here’s the problem:

- Client joins the network and starts queuing messages.

- Client: “Hey, I need the starting state of collection A.”

- Server: “I’m on message 50 now, and here’s your collection!” The server then stops the world to perform an expensive serialization operation.

- Client: “Thanks…I’ll take collections B-Z while you’re at it.”

- Server: “A little busy right now…”

- Client: “Tough luck. Do it.”

This isn’t going to scale well. As an alternative we could have the client replay all messages that ever mutated the collection, but that might require lots of time and bandwidth. Is there a good compromise that still gives us total consistency?

The solution involves persistent collections. Whenever a client needs a snapshot, the server kicks off a worker thread and uses a memory fence to hand off the reference and ensure that all updates to that version of the collection are visible. Then, the worker thread handles serialization and transmission while the server proceeds with business as usual. If we explicitly add snapshot functionality to our collection we don’t even need thread safety as the API should ensure that we’re holding an immutable reference to a specific point in time, and not just the current head of the collection.

This is a pretty awesome way to accomplish a lot of tasks, even mundane ones like ensuring that a GUI or web client displays a table that’s always in sync with the server. For more advanced use cases such as snapshot/replay based recovery we can extend this concept and have the server take a snapshot every n messages or minutes. Each time it does so the server stores a reference to the collection in a list. Then, when a client needs to get caught up or recover from an outage it can ask for a snapshot as-of a specific time/sequence number. The server would then return the most recent snapshot before the requested version, and the client would replay all subsequent messages to recover state. Datomic applies this model to the database world to greatly simplify many use cases and allow for queries against any point in history.