Accelerated FIX Processing via AVX2 Vector Instructions

Accelerated text processing via SIMD instructions

Text isn’t going anywhere as a means of storing and transmitting data. It’s pretty rare that I hear anyone speak of binary protocols for scientific data short of HD5, and frameworks such as Hadoop largely rely on CSV, XML, and JSON for data interchange. As such there’s good incentive to optimize text processing; on Intel x86 hardware, SSE and AVX instructions are ideal for the task. Both are examples of single instruction multiple data (SIMD) instructions—primitives that target vector registers for single instruction parallelism. I have a specific motivation in writing this post—the FIX protocol. However, the examples below would apply equally well to most text processing tasks.

Background on the FIX Protocol

The FIX Protocol underpins a vast ecosystem of electronic trading. It came about as an easy to implement, generic, and flexible means of transmitting orders and disseminating market data via human readable text. As FIX predates mass market HFT it addressed a different use case than what’s common in the binary protocols that emerged thereafter. At the time the ability to transmit extensible, loosely structured data outweighed performance considerations. That said, FIX still stands as the the only standardized, widely adopted protocol for both orders and market data. Most brokers and exchanges support it, even if they have a proprietary, lower latency offering as well.

FIX is a nightmare from a performance standpoint. Integers and decimals are transmitted as ASCII plain text necessitating extra bandwidth and a byte-by-byte conversion, messages aren’t fixed length, and the protocol necessitates parsing to extract meaningful business objects. Expressed as a (sloppy/partial) EBNF grammar FIX is simply:

soh ::= '0x1'

char ::= "all printable ASCII characters"

ascii_digit ::= [0-9]

value ::= char*

tag ::= ascii_digit+

field ::= tag "=" value

message ::= (field soh)+

As an example, consider: 8=FIX.4.2|9=130|35=D|…|10=168, which is in the format tag=value|tag=value… All messages

start with a “begin string” specifying the protocol version (8=FIX.4.2) and end with a simple ASCII checksum mod 256

(10=168). An extensive, informally specified grammar addresses application layer validation.

The Problem

People typically use a FIX engine to handle FIX. I’ve only described the representation of a message but FIX comes with a long list of requirements: heartbeats, reconnects, message replay, etc. Using an engine that’s reasonably performant, standardized, and well tested spares you those unpleasantries. Open source options such as quickfix are in widespread use, and there’s a long list of off-the-shelf commercial engines that are more performant/feature rich. If you’re deeply concerned about deterministic latency and have the budget, FPGAs and ASICs are the way to go.

FIX engines address a very broad use case, playing no favorites between the buy side and the sell side. They conflate many concerns: connectivity, parsing, validation, persistence, and recovery. Engines are opinionated software and the way to go if you just want to get something working. However, chances are that there’s plenty of code bloat and indirection to support a use case that you don’t care about. If you’re the initiator of an order, and not a broker or an exchange who’s responsible for maintaining FIX sessions to a wide user base, that’s especially true. On top of everything else, good luck separating your business logic from the engine’s API in a clean, zero copy fashion.

I’m in the process of designing a trading platform (many components of which I’ll open source, so stay tuned) and as such I’ve had an opportunity to revisit past sins—the handling of FIX messages being one of them. I decided to build a very simple, buy-side-optimized FIX framework that separates network, parsing, and persistence concerns. It won’t be as beginner friendly but it will put the developer back in control of things that matter: memory management, threading, message processing, and API isolation. Initial tests show that it’s an order of magnitude lower latency than most of what’s out there. That’s not a fair comparison seeing as it offers much less for the general use case, but it suits my purposes. Also keep in mind that network hops are always the big, roughly fixed cost expense.

Part 1: Parsing

Playing around with the lowest level concerns—message tokenization and checksum calculation gave me a good excuse to try out the latest AVX2 introduced as part of the Intel Haswell microarchitecture. AVX2 greatly expanded AVX integer instruction support and introduced many other floating point goodies as well. AVX gets another bump in 2015-2016 with the introduction of AVX-512. At present SSE instructions target 128 bit XMM registers while AVX uses 256 bit YMM registers. AVX-512 will introduce 512 bit ZMM registers doubling Intel’s superscalar capabilities once again.

Disclaimer: the code below is not well tested, it’s not even close to what I use in production, and it will probably only build on Linux GCC > 4.7. Furthermore, running it on any processor that doesn’t support AVX2 will merrily give you a SIGILL (illegal instruction) and kill your program. These benchmarks are quick and dirty. My test bench: Fedora 19 on a 15” late 2013 MacBook Pro (Haswell): Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-4750HQ CPU @ 2.00GHz.

We’ll start with tokenization. As a toy example, let’s count the number of equal signs = and \1 characters in a null

terminated string (this is functionally equivalent to parsing a message using a visitor pattern). I used the following

modified but real message for all of my benchmarks:

const char test_fix_msg[] =

"1128=9\1 9=166\1 35=X\1 49=ABC\1 34=6190018\1 52=20100607144854295\1 \

75=20100607\1 268=1\1 279=0\1 22=8\1 48=6640\1 83=3917925\1 107=ASDF\1 269=2\1 \

270=106425\1 271=1\1 273=144854000\1 451=-175\1 1020=959598\1 5797=2\1 \

10=168\1\0";

A canonical implementation looks something like:

/*

A simple implementation that loops over a character string, character by

character, summing the total number of '=' and '\1' characters.

*/

__attribute__((always_inline))

inline int parseNaive(const char* const target, size_t targetLength) {

int sohCount = 0;

int eqCount = 0;

for(size_t i = 0; i < targetLength; ++i) {

const char c = target[i];

if('=' == c) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == c) {

++sohCount;

}

}

return sohCount + eqCount;

}

/*

An unrolled version of the naive implementation. This serves as a baseline

comparison against vectorization by unrolling one the loop into a 16 bit stride.

A good optimizing compiler will do this for us (albeit it will probably

pick a different stride length to unroll by).

*/

__attribute__((always_inline))

inline int parseUnrolled(const char* const target, size_t targetLength) {

int sohCount = 0;

int eqCount = 0;

size_t i = 0;

if(targetLength >= 16) {

for(; i <= targetLength - 16; i += 16) {

if('=' == target[i]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 1]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 1]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 2]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 2]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 3]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 3]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 4]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 4]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 5]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 5]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 6]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 6]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 7]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 7]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 8]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 8]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 9]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 9]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 10]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 10]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 11]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 11]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 12]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 12]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 13]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 13]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 14]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 14]) {

++sohCount;

}

if('=' == target[i + 15]) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == target[i + 15]) {

++sohCount;

}

}

}

for(; i < targetLength; ++i) {

const char c = target[i];

if('=' == c) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == c) {

++sohCount;

}

}

return sohCount + eqCount;

}

const int mode = _SIDD_UBYTE_OPS | _SIDD_CMP_EQUAL_ANY |

_SIDD_LEAST_SIGNIFICANT;

/*

This implementation emits the pcmpistri instruction introduced in SSE 4.2 to

search for a needle ('=' and '\1') in a haystack (the message). It offers a

clean, vectorized solution at the cost of an expensive opcode. Each time a

"needle" is found the search index is advanced past the given index.

*/

__attribute__((always_inline))

inline int parseSSE(const char* const target, size_t targetLength) {

const __m128i pattern = _mm_set_epi8(0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0,

0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, '=', '\1');

__m128i s;

size_t strIdx = 0;

int searchIdx = 0;

int sohCount = 0;

int eqCount = 0;

if(targetLength >= 16) {

while(strIdx <= targetLength - 16) {

s = _mm_loadu_si128(reinterpret_cast<const __m128i*>(

target + strIdx));

searchIdx = _mm_cmpistri(pattern, s, mode);

if(searchIdx < 16) {

if('=' == target[strIdx + searchIdx]) {

++eqCount;

} else {

++sohCount;

}

}

strIdx += searchIdx + 1;

}

}

for(; strIdx < targetLength; ++strIdx) {

const char c = target[strIdx];

if('=' == c) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == c) {

++sohCount;

}

}

return sohCount + eqCount;

}

/*

A small modification of the parseSSE implementation in which a linear scan

is used to finish scanning over the remaining 128 byte word whenever a match

is found.

*/

__attribute__((always_inline))

inline int parseSSEHybrid(const char* const target, size_t targetLength) {

const __m128i pattern = _mm_set_epi8(0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0,

0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, '=', '\1');

union {

__m128i v;

char c[16];

} s;

size_t strIdx = 0;

int searchIdx = 0;

int sohCount = 0;

int eqCount = 0;

if(targetLength >= 16) {

for(; strIdx <= targetLength - 16; strIdx += 16) {

s.v = _mm_loadu_si128(reinterpret_cast<const __m128i*>(

target + strIdx));

searchIdx = _mm_cmpistri(pattern, s.v, mode);

if(searchIdx < 16) {

for(int i = searchIdx; i < 16; ++i) {

const char c = s.c[i];

if('=' == c) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == c) {

++sohCount;

}

}

}

}

}

for(; strIdx < targetLength; ++strIdx) {

const char c = target[strIdx];

if('=' == c) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == c) {

++sohCount;

}

}

return sohCount + eqCount;

}

/*

As we're looking for simple, single character needles we can use bitmasking to

search in lieu of SSE 4.2 string comparison functions. This simple

implementation splits a 256 bit AVX register into eight 32-bit words. Whenever

a word is non-zero (any bits are set within the word) a linear scan identifies

the position of the matching character within the 32-bit word.

*/

__attribute__((always_inline))

inline int parseAVX(const char* const target, size_t targetLength) {

__m256i soh = _mm256_set1_epi8(0x1);

__m256i eq = _mm256_set1_epi8('=');

size_t strIdx = 0;

int sohCount = 0;

int eqCount = 0;

union {

__m256i v;

char c[32];

} testVec;

union {

__m256i v;

uint32_t l[8];

} mask;

if(targetLength >= 32) {

for(; strIdx <= targetLength - 32; strIdx += 32) {

testVec.v = _mm256_loadu_si256(reinterpret_cast<const __m256i*>(

target + strIdx));

mask.v = _mm256_or_si256(

_mm256_cmpeq_epi8(testVec.v, soh),

_mm256_cmpeq_epi8(testVec.v, eq));

for(int i = 0; i < 8; ++i) {

if(0 != mask.l[i]) {

for(int j = 0; j < 4; ++j) {

char c = testVec.c[4 * i + j];

if('\1' == c) {

++sohCount;

} else if('=' == c) {

++eqCount;

}

}

}

}

}

}

for(; strIdx < targetLength; ++strIdx) {

const char c = target[strIdx];

if('=' == c) {

++eqCount;

} else if('\1' == c) {

++sohCount;

}

}

return (sohCount + eqCount) % 256;

}

The first two implementations don’t use any form of vectorization and serve as our baseline. As noted, a good compiler

will effectively unroll the first implementation into the second, but explicit unrolling serves as a nice illustration

of this common optimization. Compiling with "CFLAGS=-march=core-avx2 -O3 -funroll-loops -ftree-vectorizer-verbose=1"

shows that none of our functions were vectorized and that the optimizer left our “hand unrolling” alone in

parseUnrolled().

From the vectorization report we also see that the loop in parseNaive() was unrolled seven times. The compiler is

sparing with this optimization as unrolling comes at a cost. Increased code size leads to potential performance issues

(long jumps in a huge function can cause an instruction cache miss, which is really, really bad latency wise). Note that

by default GCC looks for vectorization opportunities at the -O3 optimization level, or whenever -ftree-vectorize is

set. However, because of its potential drawbacks, global unrolling isn’t enabled at any optimization level by default.

Setting -funroll-loops at -02 and higher will ask GCC to treat all loops as candidates for unrolling.

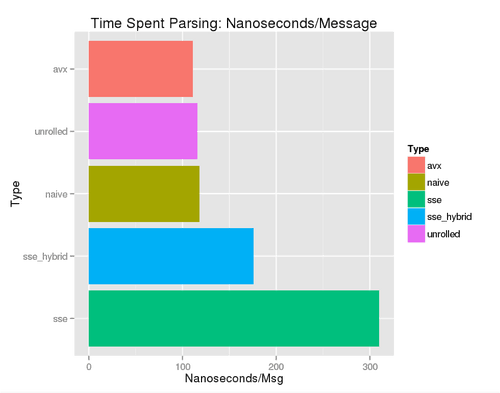

The results weren’t compelling but the “best implementation” using AVX did offer a 5% speedup over the next runner up—our hand unrolled loop. Averaging across 10,000,000 iterations yields:

There’s a good explanation for these lackluster results. On the SSE front STTNI (String and Text New Instructions)

instructions have a very high instruction latency. PCMPESTRI, emitted by _mm_cmpistri takes eight cycles to return a

result. The STTNI instruction set offers a rich set of operations via its control flag but because our query is so basic

the instruction’s overhead isn’t worth it. Worst of all, “needles” are very dense in our “haystack” so we end up

duplicating vector loads. STTNI instructions perform very well on general use cases or more complicated queries, which

is why functions such as strchr() and strlen() in glibc use them.

On the AVX front we use a simple bitmask comparison to find equal signs and SOH characters. That’s great but we’re left with a bitmask that we still have to iterate over in a serial fashion. I experimented with several approaches including iteration via LZCNT and a finer grained search than the 32-bit integer one used above. Everything that I tried, albeit not an exhaustive list, was a tie or marginally slower. The classic parallel stream compaction algorithm is, in theory what we want. However, I’ve yet to figure out an efficient way to reorder the data with vector shuffle operations. If anyone has an idea on this front I would love to hear from you.

Part 2: Checksums

Given our disappointing results on the parsing front it’s time for a win. Calculating a checksum is embarrassingly parallel (ignoring overflow, which we can for any practical FIX message) so it should lend itself to vectorization quite well. Let’s try out a few implementations:

/*

A baseline, cannonically correct FIX checksum calculation.

*/

__attribute__((always_inline))

inline int naiveChecksum(const char * const target, size_t targetLength) {

unsigned int checksum = 0;

for(size_t i = 0; i < targetLength; ++i) {

checksum += (unsigned int) target[i];

}

return checksum % 256;

}

/*

An AVX2 checksum implementation using a series of VPHADDW instructions to add

horizontally packed 16-bit integers in 256 bit YMM registers. Results are

accumulated on each vector pass.

*/

__attribute__((always_inline))

inline int avxChecksumV1(const char * const target, size_t targetLength) {

const __m256i zeroVec = _mm256_setzero_si256();

unsigned int checksum = 0;

size_t offset = 0;

if(targetLength >= 32) {

for(; offset <= targetLength - 32; offset += 32) {

__m256i vec = _mm256_loadu_si256(

reinterpret_cast<const __m256i*>(target + offset));

__m256i lVec = _mm256_unpacklo_epi8(vec, zeroVec);

__m256i hVec = _mm256_unpackhi_epi8(vec, zeroVec);

__m256i sum = _mm256_add_epi16(lVec, hVec);

sum = _mm256_hadd_epi16(sum, sum);

sum = _mm256_hadd_epi16(sum, sum);

sum = _mm256_hadd_epi16(sum, sum);

checksum += _mm256_extract_epi16(sum, 0) +

_mm256_extract_epi16(sum, 15);

}

}

for(; offset < targetLength; ++offset) {

checksum += (unsigned int) target[offset];

}

return checksum % 256;

}

/*

A modified version of avxChecksumV1 in which the sum is carried out, in

parallel across 8 32-bit words on each vector pass. The results are folded

together at the end to obtain the final checksum. Note that this implementation

is not canonically correct w.r.t overflow behavior but no reasonable length

FIX message will ever create a problem.

*/

__attribute__((always_inline))

inline int avxChecksumV2(const char * const target, size_t targetLength) {

const __m256i zeroVec = _mm256_setzero_si256();

const __m256i oneVec = _mm256_set1_epi16(1);

__m256i accum = _mm256_setzero_si256();

unsigned int checksum = 0;

size_t offset = 0;

if(targetLength >= 32) {

for(; offset <= targetLength - 32; offset += 32) {

__m256i vec = _mm256_loadu_si256(

reinterpret_cast<const __m256i*>(target + offset));

__m256i vl = _mm256_unpacklo_epi8(vec, zeroVec);

__m256i vh = _mm256_unpackhi_epi8(vec, zeroVec);

// There's no "add and unpack" instruction but multiplying by

// one has the same effect and gets us unpacking from 16-bits to

// 32 bits for free.

accum = _mm256_add_epi32(accum, _mm256_madd_epi16(vl, oneVec));

accum = _mm256_add_epi32(accum, _mm256_madd_epi16(vh, oneVec));

}

}

for(; offset < targetLength; ++offset) {

checksum += (unsigned int) target[offset];

}

// We could accomplish the same thing with horizontal add instructions as

// we did above but shifts and vertical adds have much lower instruction

// latency.

accum = _mm256_add_epi32(accum, _mm256_srli_si256(accum, 4));

accum = _mm256_add_epi32(accum, _mm256_srli_si256(accum, 8));

return (_mm256_extract_epi32(accum, 0) + _mm256_extract_epi32(accum, 4) +

checksum) % 256;

}

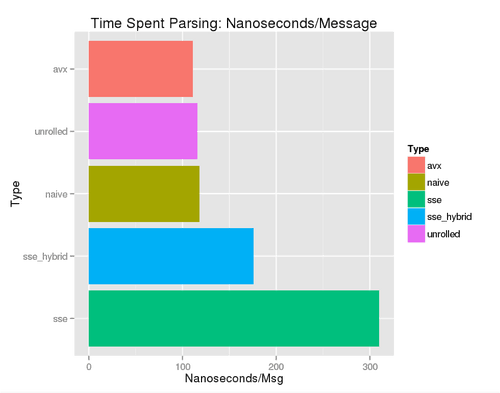

And the results:

The first thing we note is that GCC is pretty good at its job. With vectorization enabled we get code that’s a dead tie with our first hand optimized implementation. Without vectorization enabled it’s no contest. And this time around, we beat GCC’s vectorized code by a factor of two.

First let’s look at what GCC did to our baseline implementation. Picking through the disassembly reveals that the

compiler did indeed use AVX. In short the function spends some time 16-byte aligning memory (unaligned loads to vector

registers are slower, but on modern hardware there’s very little difference sans pathological cases) before entering a

loop where our vector is padded, sign extended, and added as packed double words on the upper and lower half of a YMM

register (most AVX instructions treat a 256 bit YMM register as two independent 128 bit ones):

40106e: c4 e2 7d 20 c1 vpmovsxbw %xmm1,%ymm0

401073: c4 e3 7d 39 ca 01 vextracti128 $0x1,%ymm1,%xmm2

401079: c4 e2 7d 20 da vpmovsxbw %xmm2,%ymm3

40107e: c4 e2 7d 23 e0 vpmovsxwd %xmm0,%ymm4

401083: c4 e3 7d 39 c5 01 vextracti128 $0x1,%ymm0,%xmm5

401089: c4 e2 7d 23 f5 vpmovsxwd %xmm5,%ymm6

40108e: c5 cd fe fc vpaddd %ymm4,%ymm6,%ymm7

…pattern repeated with cruft

Our hand implemented version is easier to follow and translates directly from what we wrote so no surprises here:

401407: c5 dd 60 e9 vpunpcklbw %ymm1,%ymm4,%ymm5

40140b: c5 dd 68 f1 vpunpckhbw %ymm1,%ymm4,%ymm6

40140f: c5 d5 fd fe vpaddw %ymm6,%ymm5,%ymm7

401413: c4 62 45 01 c7 vphaddw %ymm7,%ymm7,%ymm8

401418: c4 42 3d 01 c8 vphaddw %ymm8,%ymm8,%ymm9

40141d: c4 42 35 01 d1 vphaddw %ymm9,%ymm9,%ymm10

Now for the fun part. In avxChecksumV1() we used the PHADDW instruction to quickly accomplish what we wanted—a sum

across each 32 byte chunk of our FIX message. SIMD instructions are optimized to operate “vertically,” meaning that

operations such as , , are efficient, and

horizontal operations such as a prefix sum are not. Almost all of the

AVX/SSE add instructions have only one cycle of latency and execute as one

micro operation. HADDW requires 3-4 cycles and 1-2 -ops

depending on its operands. Eliminating it should pay dividends.

As noted in the comments for avxChecksumV2() we can get free unpacking via _mm256_madd_epi16, which emits the

PMADDWD instruction (one cycle, two -ops). Evidently GCC has a better understanding of what we’re trying to do

this time around as it unrolls the inner loop and reorders our instructions to minimize loads and better optimize

register use:

401aca: c5 1d 60 e9 vpunpcklbw %ymm1,%ymm12,%ymm13

401ace: c5 15 f5 f8 vpmaddwd %ymm0,%ymm13,%ymm15

401ad2: c5 1d 68 f1 vpunpckhbw %ymm1,%ymm12,%ymm14

401ad6: c4 c1 25 fe d7 vpaddd %ymm15,%ymm11,%ymm2

401adb: c5 8d f5 d8 vpmaddwd %ymm0,%ymm14,%ymm3

…pattern repeated with cruft

We note that there’s roughly a factor of five difference between the unvectorized naive function and our best implementation that uses six AVX instructions per loop. That sounds pretty reasonable as we’re working with 32 characters at a time and each instruction has one cycle of latency, so by Little’s Law our max speedup is .

Closing Thoughts

Having worked through these examples it’s easy to see why FPGAs and ASICs have an advantage in this space. Processing and validating tag/value pairs is a simple, highly parallel problem that lends itself well to a hardware implementation. Hundreds of thousands of operations can be carried out in parallel with virtually zero latency jitter. That does however come at a cost—as demonstrated above we can tokenize a message in ~110ns, which is roughly twice the time that it would take a CPU to read from main memory (or in this case an FPGA coprocessor over a DMA bus). Unless the FPGA/ASIC does application layer validations as well, having an external process or piece of hardware parse a message for the sake of handing you a packed structure probably isn’t worth it. The hardware value add comes from deterministic networking and highly parallel risk checks.

FIX is about as simple as it gets so SSE/AVX has much more to offer when the use case is more complex. Furthermore, as

noted before, the distance between tag/value pairs is small, meaning that we don’t get the same sort of boost that we

would expect when searching for sparse delimiters in structured text. I came across a good article on a more general

problem, SSE UTF-8 processing, when writing this. As a side

note, for sufficiently long integers, specializing atoi() via

fused multiply-add instructions might pay

dividends.